Illustrated Talk by Laura Dunlop, K.C. and Emma Boffey

Good evening…before we begin, I’d like to acknowledge the support and encouragement with this project from the Lord President and the Dean and the huge organisational backup from Scott Brownridge, Fay McIsaac and Andrew Tregoning, who have been magnificent as always. I’d also like to record that the other members of the planning group: Ann Inglis, Emma Boffey and Jane Condie have been unstinting in attending many meetings as we all tried to think of everything. Jane is not speaking here tonight, but part of her massive research contribution is in a longer PowerPoint, with many fascinating slides, which will run after we finish. With these thoughts, let’s turn to look at how it all happened. Emma, OTY.

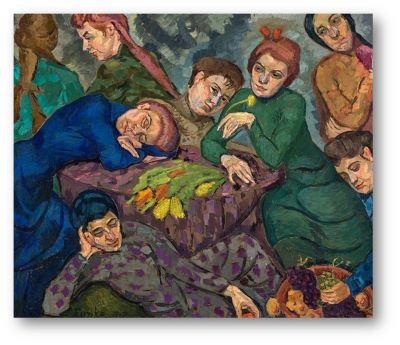

Is this how it starts?

This picture is ‘Women Dreaming’ by German painter Helene Funke. She painted it in 1913. In the Belvedere Art Gallery in Vienna, where it hangs, we learn that women were not allowed to attend art academies and Helene had to surmount many obstacles to achieve her goal of becoming a painter. Sound familiar?

Was Margaret Kidd a woman dreaming in 1913? She would have been 13 at the time, so maybe. But the omens were not encouraging, with the Court of Appeal deciding in 1913 in Bebb v the Law Society that women were not ‘persons’ under the Solicitors Act 1843.

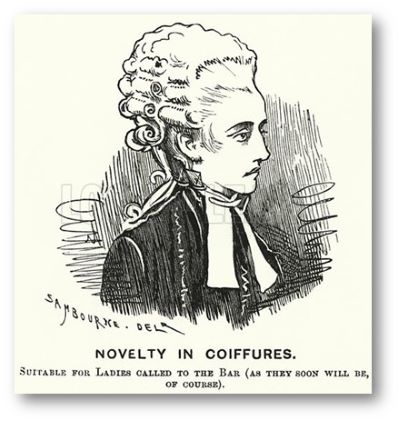

Or perhaps this is how it starts.

This is a Punch cartoon from 1875. Six years earlier, the Edinburgh Seven (Sophia Jex Blake and others) had begun studying medicine at Edinburgh University. So maybe that’s when it starts – a progression from wider social change in the 19th C. As so often, there seems to be a fascination with appearance. Novelty in hairstyles, cries Punch. A woman in a barrister’s wig, a coiffure suitable, we are told, for ladies called to the Bar, ‘as they soon will be, of course’.

Not that soon – almost 50 years later in fact. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 certainly made it possible, after Bebb. The first woman to be called to the Bar of England and Wales was Ivy Williams, in May 1922. It was, she said, ‘the dream of her life’. She never practised, however, instead teaching law at Oxford.

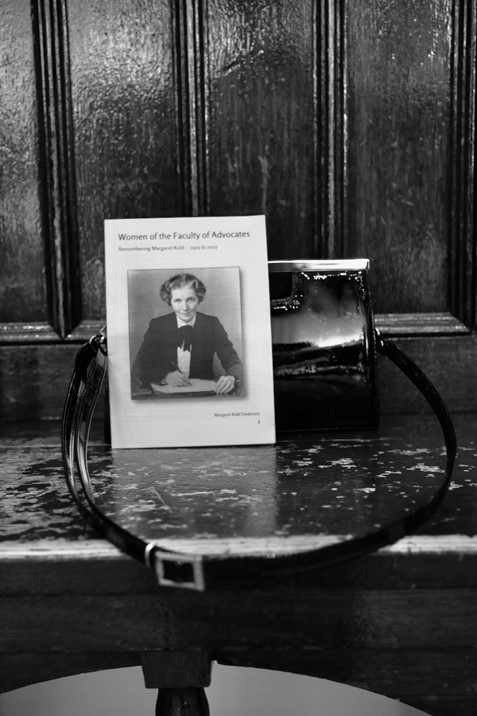

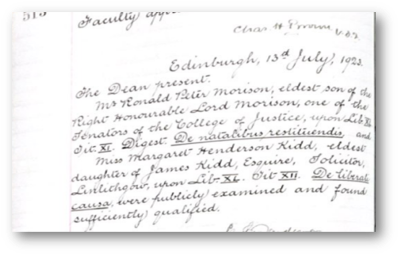

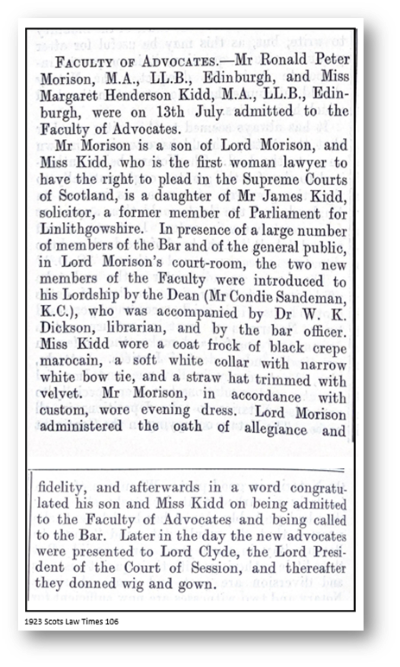

In 1923, Margaret Kidd was the first woman to call in Scotland. She was the eldest child of Janet Turnbull and James Kidd, a solicitor, whose firm was Peterkin and Kidd in Linlithgow, which still operates today. We are delighted that Tonia McFarlan, partner with Peterkin and Kidd, is here with us tonight. Margaret had 5 brothers and 3 sisters. She was educated at Linlithgow Academy, and we are also delighted that we have Sixth Year pupils Morgan, Libby, Beth and Isla from the school here tonight. Margaret studied for an MA and LLB at Edinburgh University, graduating finally in 1922. Margaret devilled to Mr MacGregor Mitchell, who went on to join the bench as Lord MacGregor Mitchell. Behind us, we have a photograph of the Faculty Minute book, which records Margaret’s admission to the Faculty on 13 July 1923, calling at the same time as Ronald Morison.

In reports of the occasion, the theme of appearance features again. The Scots Law Times – displayed here – tells us … “Miss Kidd wore a coat frock of black crepe marocain, a soft white collar with narrow white bow tie, and a straw hat trimmed with velvet. Mr Morison, in accordance with custom, wore evening dress…”

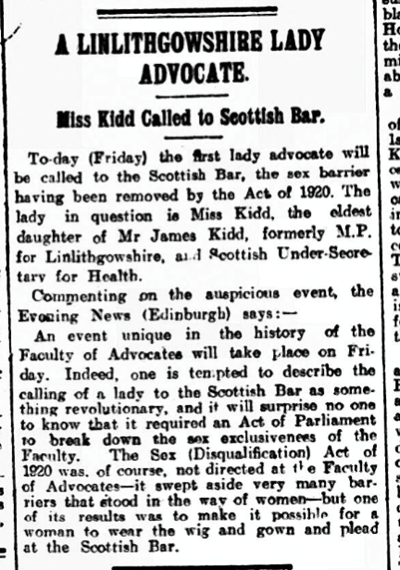

The Linlithgowshire Gazette carried a piece (culled from the Edinburgh Evening News) which includes the observation that ‘one is tempted to describe the calling of a lady to the Scottish Bar as something revolutionary and it will surprise no one to know that it required an Act of Parliament to break down the sex exclusiveness of the Faculty. The Sex Disqualification Act …swept aside very many barriers that stood in the way of women’. It may be that those barriers had obstructed Margaret’s first choice – the biography in Scotland’s People states her first choice of career as the Foreign Office, but the then Permanent Secretary, Mr Eyre Crowe, “was opposed to women”, so instead she decided to follow her father and go into law. It was also the case that her father wanted his eldest son to follow him into the firm, rather than Margaret. That was how it was in 1923.

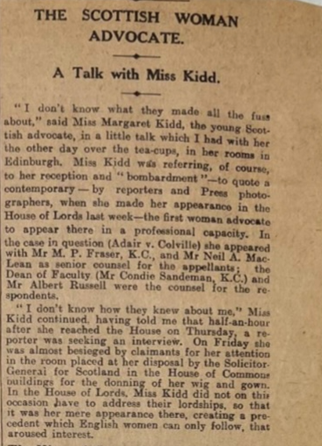

In 1926, Margaret became the first woman to appear in a case in the House of Lords. Here she is, in a cutting from an unidentified newspaper of the time, kept in the Edinburgh University archive of information on their graduates.

The event also attracted the attention of an unidentified journalist, who wrote this article, which was also in the University archive. He or she wrote it after taking tea with Miss Kidd in her rooms in Edinburgh. “I don’t know what they made all the fuss about” said Margaret, referring to her appearance in London last week.

And her appearance in the other sense is also mentioned again – we learn that Miss Kidd’s wig covers “a head of neatly shingled hair”. When asked what made her think of becoming an advocate, she reportedly said “I just sort of drifted into it” – no mention of the family firm or the Foreign Office. In public speaking, we’re told, she appreciates the need to hold the attention of the audience, “there being fewer women who have this gift than there are men”. We don’t know whose words those are, though we can see that particular topics appear to have been put – for example, regarding the alleged lack of logic in women, on which Miss Kidd is said to hold strong views. “A trained woman, she holds, can be even more logical than a trained man”. And dress (again!) in her view “should be plain and dignified, otherwise it is apt to interfere with the effect of a woman’s speech”. Reading this reminded me of Lady Dorrian’s story about the photo of herself and her fellow women dressed with dignity and protesting to the Dean about a suggestion to the contrary.

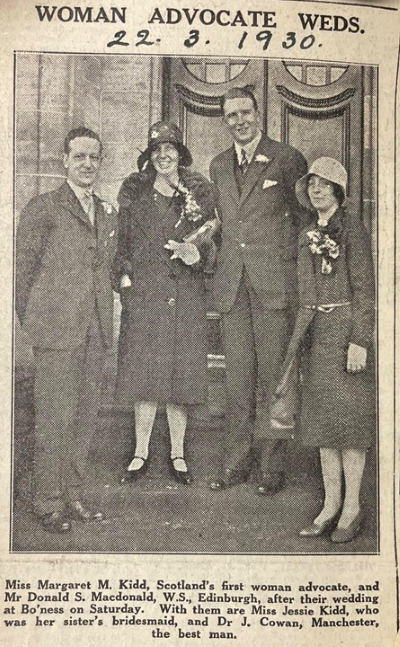

Margaret stood for Parliament in 1928, following her late father who had been Unionist MP for Linlithgowshire. Lost to Emanuel Shinwell. In March 1930, she married Donald Macdonald, a writer to the Signet. Here they are, behind us, in a photograph taken on their wedding day, which is retained by the University Archive. They had a daughter, Anne, who sadly passed away last year in Cambridge. She knew of our initiatives, and we are delighted that Anne’s daughters and her granddaughter are here tonight.

In 1948 Margaret became the first woman in the UK to take silk.

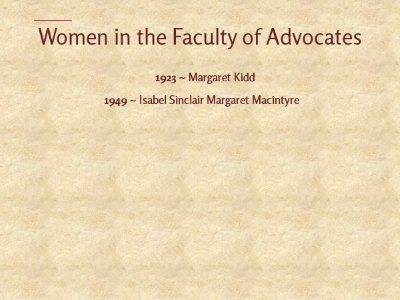

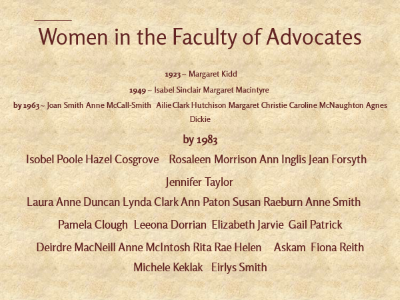

Soon, she gained two sisters in law with the admission to Faculty of Isabel Sinclair and Margaret Macintyre, who called in July 1949, a mere 26 years after Margaret had joined. We don’t have information about Margaret Mcintyre unfortunately.

Isabel had been a journalist on the Herald and rose to a high position on the paper during the War. When the men came back, it was assumed that she would be demoted, which she was not prepared to accept. In similar vein, she made it clear that, once called, she expected to take lunch in the (male) advocates’ lunch room. She was told that would not be allowed. (This does make me wonder where Margaret Kidd ate her lunch from 1923). On the day Isabel called, she marched in and sat down. That was that.

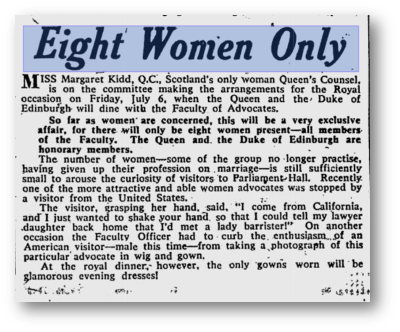

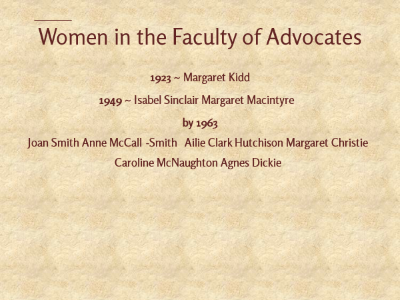

Numbers grew slowly. Here is a piece from the Glasgow paper the Bulletin, from June 1956. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh are to dine with the Faculty of Advocates. Present will be 8 women members, “although some of them no longer practise, having given up their profession on marriage”.

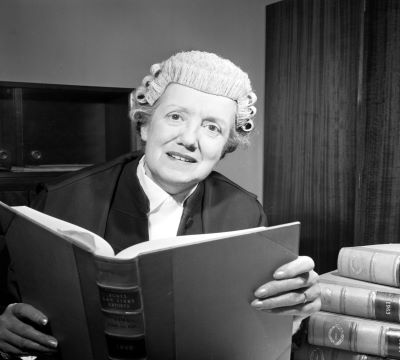

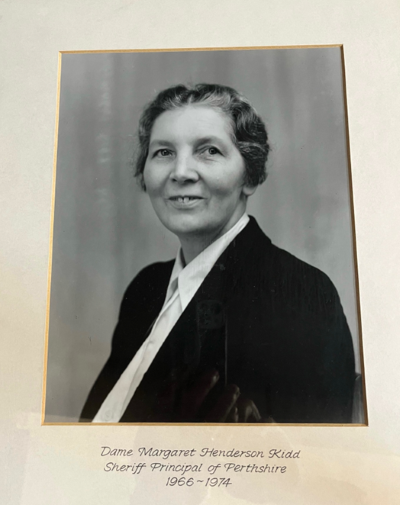

Margaret was editor of the Court of Session law reports of the Scots Law Times between 1942 and 1976. She became Keeper of the Advocates Library in 1956, and served until 1969, the only female office bearer until Lady Stacey became Vice Dean in 2004. Margaret was also appointed Sheriff Principal of Dumfries and Galloway in 1960 and then of Perthshire between 1966 and 1974. Here she is, in a photo that still hangs in Perth Sheriff Court. She died in 1989, having become a Dame. When she spoke at Glasgow University in 1930, the Scotsman reported ‘she did not think that she had been so successful as she would have been had she been a man’. Did she hold this view at the end of her career?

As for other judicial appointments – Hazel Cosgrove was the first woman to sit on the Court of Session bench as a temporary judge, then becoming a Lord Ordinary in 1996. Hazel had been the eleventh woman advocate, having called in 1968. It took until the night before she became a judge for it to be confirmed that she would not have to be addressed as My Lord. Here she is on her calling day in 1968, and as she appears in this very Hall. Hazel is the second most senior surviving female advocate. We are sorry that neither Hazel, nor Isobel Poole, who called in 1964, is able to join us tonight. How wonderful it is though that we have Ann Inglis, the third most senior surviving female advocate, here with us. Over the last few months, Laura, Jane and I have had the great privilege to spend time with Ann, typically over tea after court. It has been a joy to hear your story Ann and have practice in the 1970s and 1980s recreated for us through your memories.

Back to judicial appointments. Today, there are now 56 women who sit on the sheriff court bench and 9 on the Court of Session bench.

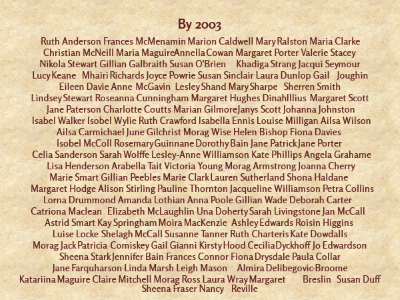

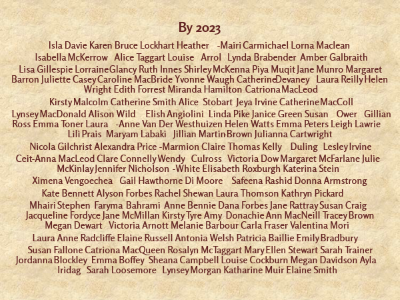

Roll call – first few individually then at 20 year intervals.

What have we noticed?

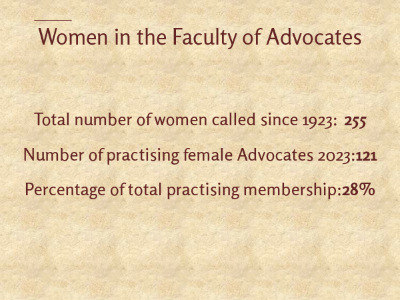

There have been 255 women called since 1923 – 4 more next week. Number is lower than the number of men in practice today. There is not much in it (313 men in practice). And in fairness - since we are advocates - the better comparison would be between 255 and however many men have called since 1923 – not an easily ascertainable number, but significantly higher than 255.

If the intake at university law schools has been around 50:50 since at least the late 1970s, why do we not see that reflected in Faculty? Ten years ago the percentage of female members was 26%, today it is 28%. Since this is a celebration, not a lament, let’s note that it’s moving in the right direction, but there’s a way to go.

And this - we have been struck by how difficult it was, for many of the women whose stories we have looked at. Difficult overall, difficult in specific respects or a bit of both. Some of the comments made to or about women advocates relayed to us are unrepeatable, both for their content and to spare the blushes of those who made them. The women must have had formidable diplomatic skills and such determination.

And finally this. Diversity goes beyond the male/female metric. It extends to other underrepresented groups. It remains harder for people with particular backgrounds and/or characteristics to have a career in law, very much including at the Bar. We, those of us who followed in the footsteps of others, recognise the need to pay it forward. That is why we’re raising money for LawScot Foundation and for Womankind Worldwide, very different organisations but part of the Equality and Diversity landscape, in Scotland and globally.

And as we do that, here, tonight, each of us should think of those who came before us, and who made it easier for us, a lot of whom are here tonight. Margaret, I hope you’re not looking down and thinking ‘I don’t know what they’re making all the fuss about’. With dignified fuss, we’re thanking you, Margaret, and all the other pioneers as well.